ST. EMMELIA WEST CONFERENCE: “HAVE FAITH”

ST. NICHOLAS RANCH, DUNLAP, CALIFORNIA

APRIL 19-22, 2018

Venerable Fathers, Esteemed Colleagues, Brothers and Sisters,

Christ is Risen!

It is an honor and a joy to join you, my fellow Orthodox home-schoolers, here today in this beautiful retreat center and near the Monastery of the Theotokos the Life-Giving Spring.

I would like to thank the Antiochian Archdiocese Department of Homeschooling and Fr. Noah Bushelli, as well as the St. Kosmas Orthodox Homeschool Association and Christine Hall, for the invitation to speak to you today.

The title of my talk is, most likely, a little disorienting for many of you. I am sure you all know what patristic means, but what does “post-Patristic” mean? The term itself is used in the sense of relativism, partial or total questioning, re-evaluation, a new reading, or even the transcendence of the thought of the Fathers of the Church.

When we speak of post-Patristic theology or theologians this refers to a contemporary movement among a small but unfortunately growing segment of academic theologians, mainly in Greece and America, who are calling on the Church to, among much else, “move beyond the fathers” of the Church, to “reinterpret our dogmatic teaching,” and to consider all heterodox Christians as a part of the One Church. (1)

According to Professor Demetrios Tselingides:

“This movement of so-called “post-Patristic” theologians which has appeared in recent years, is organically embedded in [today’s] broader, secularized, theological climate, and particularly in the spirit of Ecumenism itself... Certainly, this movement also has Protestant influences, which are particularly clear in the scientific nature of the attitude of the “post-Patristic” theologians to the theological teaching of the Holy Fathers.” (2)

The two most basic presuppositions which “post-Patristic” theology/theologians ignore are:

1. That the experience of Spiritual Life in Christ in the Church is the foundational presupposition of theologizing in an Orthodox and delusion-free manner.

2. Orthodox and delusion-free theology is only produced by those who have been cleansed of the impurity of their passions and, moreover, those who have been enlightened by the uncreated rays of divinizing Grace.

When holiness or even Orthodox theological methodology of “following the holy Fathers” is set aside, “the adoption of theological reflection and speculation is inevitable.” (3) Here is where the post-patristic theologians and the infamous Barlaam of Calabria converge “in a theology which is anthropocentric and has as its criterion selfvalidating reason.” (4)

Let’s refresh our memory a bit about Barlaam and his theology. The patrologist Panagiotis Chrestou explains:

“Barlaam bore the influence of the Renaissance, which began to rise at this time, and he considered the revelation of God to be static, limited to biblical times, and he denied that it existed in the current life of the Church, namely the experience of the monks. At the same time he sought a new authenticity, outside of Christianity, personified by the great philosophers of ancient times.

He thus explained the revelation of God based on Greek philosophy and not on the basis of the hesychastic tradition, which survived vibrantly in the Eastern Christian Roman Empire, especially Mount Athos. This is the reason why Barlaam was in opposition to Athonite monasticism, as it was expressed by Saint Gregory Palamas.” (5)

“Just as Barlaam and his followers doubted the uncreated nature of the divine light and divine grace, so too contemporary “post-patristic” theologians effectively ignore the uncreated and, therefore, enduring character of the sanctity and teaching of the Godbearing Fathers, whom they attempt to replace, as regards teaching, by producing their own original theology. This is not a battle against the Fathers, of an external nature, but in essence a battle against God, because what makes the Fathers of the Church really Fathers is their uncreated sanctity, which, indirectly but to all intents and purposes, these theologians set aside and cancel out with their “post-Patristic” theology.”

You are probably all wondering, that is all fine and good, but what does it have to do with homeschooling our children? I am glad you asked. Allow me to connect the dots.

Two main characteristics of Barlaamism that we see re-emerging today are:

• The interpretation of Holy Scripture based on philosophical and dialectic reasoning as well as thoughtful analysis and not on the living hesychastic experience.

• The view that theology, or the knowledge of God, is the objective experience of the senses, the imagination and logical processes, and not the fruit of personal experience, which is how the hesychast monks experienced it.

This idea that one can make progress on the path of salvation, or that it is even obtained through the ascent of the rational intellect to the knowledge about God, is ever so slightly creeping into Orthodox homeschooling rhetoric, most surely unbeknownst to most.

Allow me to give you a few examples:

1. The direct association of education, study and reflection, with theosis, as if the former were means to the later.

2. The idea that the goal of our reading and writing and rhetoric is theosis, again implying the one leads to the other.

3. The putting of the the Holy Tradition of the Fathers on equal footing with the tradition of Ancient Greece, and claiming that both can help train us to overcome the passions.

4. And, finally, the idea that education is itself a means by which we can overcome the passions, as opposed to a preparatory step, much like, as the Apostle Paul writes, “the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith, after which “we are no longer under a schoolmaster” (Gal 3:24).

Keep these four examples in mind as we now turn to look at the approach of the Holy Fathers to Classical Education.

1. The Fathers of the Church and Classical Education

The Fathers of the Church are today often held up as great examples of the indispensability of including pagan, classical literature in Christian education. Undoubtedly, some Fathers were well versed in classical literature and philosophy, perhaps as few of their contemporaries. Of this, no one can doubt.

Did, however, the great hierarchs of the Church become great theologians because of their classical education? Or, were their years spent in reading pagan philosophy and literature a prerequisite to become great theologians?

If one remembers the famous patristic saying, "If you are a theologian you truly pray. If you truly pray you are a theologian,” (6) the answer is apparent. A better question is: did the Great Hierarchs use their pagan education as a tool in their pastoral and apologetic work for the upbuilding of the Church? The answer to this is, of course, yes.

The Fathers of that age were shepherds of their rational flocks and indeed the entire Church at a time of great change, straddling, as it were, the outgoing Pagan world and the rising Christian empire. Their pastoral task was to speak of heavenly truths to earthbound wise-men in terms and a language which they understood. In order to understand their engagement with what we now call the “classical world” and its philosophy and mythology, it is crucial always to have this pastoral context in mind. In particular, one must understand that they were first of all approaching pagan, nonChristian culture and literature kat’oikonomia or according to pastoral condescension and not in search of the knowledge of God. Their employment (and transformation) of philosophical terms and ideas was not an end in itself but chiefly a means by which to bring uninitiated men to "the full knowledge of the truth (2 Tim. 3:7).

2. Two Types of Wisdom

In the writings of the Three Hierarchs, but also in the epistles of the Apostles Paul and James, and indeed the entire patristic tradition, there are two types of wisdom:

• ἄνωθεν, from above (or divine and true) and

• θύραθεν, from without (or human and worldly)

Each type of wisdom has limits as to its development, its aims and the means by which it is acquired.

The wisdom which comes from above (ἄνωθεν), from God, by revelation, is obtained by the enlightenment of the Holy Spirit. It is not limited, as is human knowledge. God Himself is revealed in His divine energies (actions). His mysterious presence in creation is inscrutable. It cannot be subjected to human inspection and proof. Man either receives God's mysteries with faith (trust), and sees that "God is good," or he rejects them.

The ἄνωθεν wisdom leads man to salvation, to regeneration, to taking man from the image to the likeness of God, to his perfection. Divine wisdom makes the passionate, impassive, the earthly, heavenly, the mindless, Godly-minded, the mortal, immortal.

The wisdom which comes from men, or θύραθεν, is obtained by human means, with study and reflection. Within human, θύραθεν, wisdom, the mind is taught to judge, to meditate upon, to follow principles and human rules of logic, in order to examine the earthly, the created. It cannot, however, thereby judge and examine that which is from above, and that which is uncreated (See: 1 Cor. 2: 6-16)

The following passage from the Apostle Paul’s epistle to the Corinthians is very enlightening for us in our examination of the two wisdoms:

“Howbeit we speak wisdom among them that are perfect: yet not the wisdom of this world, nor of the princes of this world, that come to nought: But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, even the hidden wisdom, which God ordained before the world unto our glory: Which none of the princes of this world knew: for had they known it, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory. But as it is written, Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him. But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God. For what man knoweth the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? even so the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God. Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the spirit which is of God; that we might know the things that are freely given to us of God. Which things also we speak, not in the words which man's wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual. But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned. But he that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself is judged of no man. For who hath known the mind of the Lord, that he may instruct him? But we have the mind of Christ.” (1 Cor 2:6 - 16)

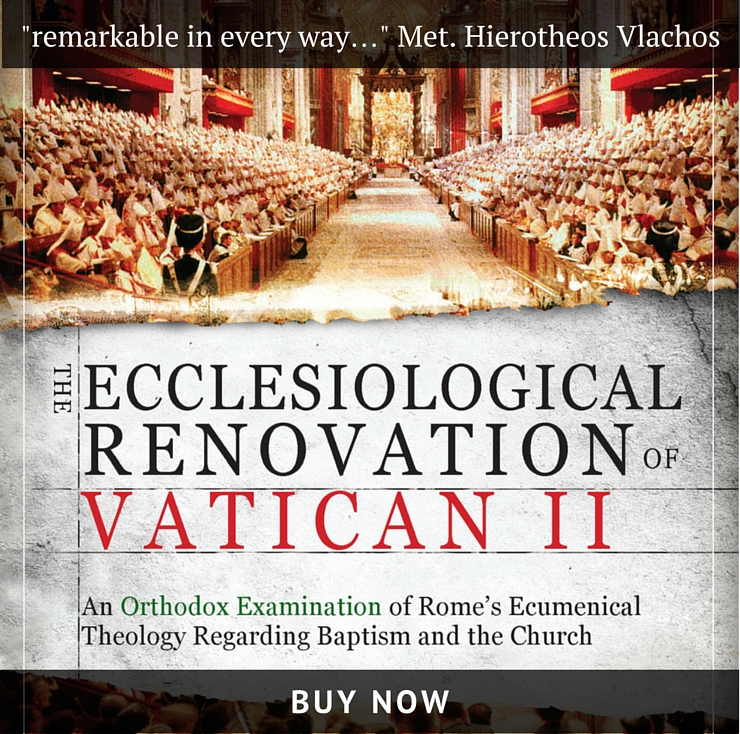

Hence, this θύραθεν or worldly wisdom is not necessary for salvation and must not become an end in itself. Contrast this with the thinking of Barlaam, as summarized by Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos:

“Barlaam gives priority to "outer wisdom" or philosophy, which even monks should seek, because only through human wisdom can we achieve dispassion, to approach perfection and sanctification. This is because he considers Greek education to be a gift from God similar to the revelation given to the Prophets and Apostles.” (7)

If worldly wisdom cannot be claimed as a means to salvation, it can, however, cooperate with and assist the heaven-sent (ἄνωθεν) wisdom toward the supreme aim of our salvation. It should been seen as a tool, and its value, then, lies in its use and it depends upon the proper perspective and disposition of the one employing it, whether or not he has respect for the things of God, according to the psalmist, "the beginning of wisdom is the fear of God (Psalm 110/11:10).

In this perspective, then, we can see that the Holy Fathers' use of the terms and ideas put forward by the human wisdom of their day was a pastoral tool, a pastoral condescension - with full respect, but also full knowledge of the limits of that wisdom.

When classical educators look for Patristic support for, as one writer put it, seeking “the face of God” in pagan literature, they cite first and almost exclusively St. Basil the Great. In his famous "Address to Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature" the Saint wrote the following:

“Now, then, altogether after the manner of bees must we use these writings, for the bees do not visit all the flowers without discrimination, nor indeed do they seek to carry away entire those upon which they light, but rather, having taken so much as is adapted to their needs, they let the rest go. So we, if wise, shall take from heathen books whatever befits us and is allied to the truth, and shall pass over the rest. And just as in culling roses we avoid the thorns, from such writings as these we will gather everything useful, and guard against the noxious.” (8)

First of all, it is apparent here that far from rushing indiscriminately, headlong into pagan literature the Saint is selectively lighting on that which is redeemable, salvaging what he can from the noxious writings of “natural men” (1 Cor. 6:14-16).

Secondly, although it is not debated that St. Basil knew classical Greek literature as a whole very well, it needs to be said his education was obtained long before his initiation into Christ and it was a providential preparation and apologetical tool to better wield the ultimate weapon, the Truth revealed in Christ and manifest in the Holy Scriptures.

What is often overlooked, however, in this discussion is that the Fathers had little choice in the matter. In the Fourth century the mainstream education curriculum was based on Ancient Greek literature and thus the youths’ encounter with it, including mythology and other fiction, was a given. St. Basil had no choice but to prepare young people for the texts that they were going to encounter.

We need to remember that St. Basil and his friend, St. Gregory of the Theologian, although raised in Christian homes, had undergone this education before being baptized and although both were quite familiar with pagan myths, they harshly ridiculed them. (9) Reading pagan fiction (mythology) was, then, not a choice made in adulthood, post baptism.

St. Basil himself in Epistle 223 (PG 32, 824AB) writes that he wept many tears for the days of his adolescence which he had spent in vain, studying philosophy, the “wisdom of this world that God made foolish” (1 Cor. 1: 20). It is only logical to assume that what he writes concerning philosophy applies much more to mythology (or fiction):

Much time had I spent in vanity, and had wasted nearly all my youth in the vain labour which I underwent in acquiring the wisdom made foolish by God (cf. 1 Cor. 1:20). Then once upon a time, like a man roused from deep sleep, I turned my eyes to the marvellous light of the truth of the Gospel, and I perceived the uselessness of “the wisdom of the princes of this world, that come to naught” (1 Cor. 2:6). I wept many tears over my miserable life and I prayed that guidance might be vouchsafed me to admit me to the doctrines of true religion. First of all was I minded to make some mending of my ways, long perverted as they were by my intimacy with wicked men. Then I read the Gospel, and I saw there that a great means of reaching perfection was the selling of one's goods, the sharing them with the poor, the giving up of all care for this life, and the refusal to allow the soul to be turned by any sympathy to things of earth. And I prayed that I might find some one of the brethren who had chosen this way of life, that with him I might cross life's short and troubled strait. And many did I find in Alexandria, and many in the rest of Egypt, and others in Palestine, and in Cœle Syria, and in Mesopotamia. I admired their continence in living, and their endurance in toil; I was amazed at their persistency in prayer, and at their triumphing over sleep; subdued by no natural necessity, ever keeping their souls' purpose high and free, in hunger, in thirst, in cold, in nakedness (cf. 2 Cor. 11:27) they never yielded to the body; they were never willing to waste attention on it; always, as though living in a flesh that was not theirs, they showed in very deed what it is to sojourn for a while in this life, and what to have one's citizenship and home in heaven. All this moved my admiration. I called these men's lives blessed, in that they did in deed show that they “bear about in their body the dying of Jesus” (2 Cor. 4:10). And I prayed that I, too, as far as in me lay, might imitate them.

What the Saint describes here is essentially his inner, spiritual conversion and coming to the knowledge of the truth of life in Christ, a process which led away from the vanity of the worldly wisdom of “natural men” to the wisdom from above found in the ascetics and under the direction of a spiritual father.

3. The Diachronic Witness of the Fathers on the Superiority of Christian Wisdom

Throughout the history of the Church the stance of the Saints’ has been consistent: they commend the study of classical learning, with discernment, but give clear precedence to Christian wisdom. The example of St. Photios the Great is indicative:

While supporting classical learning along side of spiritual formation St. Photios advises:

“Give yourself over to our own noble muses too, seeing that these differ from those of the Pagans as much as freemen differ from slaves and as much as truth differs from flattery. . . . True, divine gladness, that which is proper to man. . . Springs from the Holy Scriptures and our zealous study of them.” (10)

There is a clear hierarchy of things pertaining both to man’s make-up and to his education and formation. It is no accident that the Lord chose fishermen rather than Pharisees as his disciples, thus pointing to the superiority of His Grace over the power of the human mind. St. Photios, responding to a question concerning how the illiterate Apostles managed to overcome Pagan rhetoric, writes:

“If the mind is greater than the written word, and divine grace is - by an incomprehensible measure - greater than the mind, then you ought not at all to be surprised if the Apostles, who possessed the greater [mind] and the greatest [divine grace] completely overwhelmed those - I mean, the rhetors and philosophers - who showed great arrogance on account of their possession of the least.” (11)

One needs to always have this hierarchy in mind, both when reading the Scriptures and Fathers and teaching their children, otherwise he will be misled into believing that, unlike the Holy Apostles, the Great Hierarchs were “great” because of their worldly education and not their spiritual initiation.

Another example brought forth by St. Photios to illustrate this hierarchy and the pastoral condescension of the Saints is the stance of the Apostle Paul when he spoke to the pagans in Athens concerning the altar of an unknown god (Acts 17:23). Fr. Theodore Zisis summarizes St. Photios the Great’s commentary on this as follows:

“The Apostle Paul’s use of classical idioms..does not mean that he somehow abandoned his basic position that the truth must be built upon spiritual realities alone ‘comparing spiritual things with spiritual,” for it is indeed he who calls ‘the Mosaic law itself chaff, when compared to the supreme wisdom of Christ.’ It would be truly unworthy of Paul’s divine illumination were he to ‘compose truth from myths.’ On the contrary, here is simply condescending to the Athenians’ weakness, to their spiritual infancy, which would not allow them to see the truth directly, thereby pedagogically preparing them so that the truth’s rays might illumine their minds.” (12)

4. Coming to the Knowledge (Epignosis) of the Truth

The Fathers’ primary task, then, as shepherds and catechists was not simply to teach, much less to inform, but rather to initiate a proud and rationalist world into the Mystery of the Gospel. This is the heart of the work of the catechist or teacher: to initiate his disciple into the event of Pentecost. In fact, the Greek word for catechism, ῾κατήχηση῾, is formed from the event of Pentecost, when a sound (ήχος) came down (κάτω) from heaven.

The aim of the Fathers' pastoral work was not one of moral improvement or rational development but of supra-rational communion with the Holy Trinity, which presupposes repentance, purification and initiation. To paraphrase the Apostle of Love, "that which they had seen and heard from the beginning," that of which they had επίγνωσης, or first-hand, experiential knowledge, that they declared unto the 4th century pagan world, "that they may also have communion" with them and the Holy Trinity.

The Holy Fathers did not believe that salvation was simply a matter of obtaining γνώσης (knowledge), but, rather, επίγνωσης, experiential knowledge of God Himself, of His uncreated energies, which meant first of all entry into the Church and initiation into the life in Christ. This initiation was a process of purification and illumination, of divesting oneself of the passions and heretical ideas of the rationalists and investing oneself with the mind of Christ and Orthodox phronema or mindset; of putting off the old man of sin and death and putting on the resurrected and ascended humanity of Christ.

Enlightenment for the Holy Fathers did not chiefly mean the acquiring of knowledge ABOUT God, ABOUT the truth in terms of ideas - although this can be helpful and an important preparatory step - but rather all learning was meant to lead to personal, experiential knowledge of the Truth Incarnate. They undoubtedly encountered in their day that which the Apostle Paul describes as a characteristic of the last days, namely, men who had "the form of piety" but denied "the power thereof," who are "always learning" but "never able to come to a full knowledge (επίγνωσης) of the truth" (2 Tim. 3:5,7).

This is a characteristic of the heretical man: having lost the ethos or way of life he innovates and shipwrecks with regard to the dogma or truth of Christ. Or vice-versa: having ignored or devalued the dogmas of the Church as the basis of spiritual life, he soon falls into a worldly, grace-obstructing way of life.

Thus, given the ever-imminent threat of heresy, much of the Fathers' pastoral and catechetical work consisted of the struggle against heresy and heretically-minded men.

The heretics used worldly philosophy to logically examine and pronounce upon the things of God which surpassed logic - and they did this without the necessary prerequisite of experience. Our Saints fought heresy at its root, stressing in word and deed that dogmatic Truth and the Way or Ethos of Christ are inseparable, two sides of the same coin; that there is no possibility for the autonomy of one from the other; and that the loss of one is the loss of the whole.

As St. John Chrysostom wrote:

"There is no benefit from a pure life when one professes heretical dogma and, likewise, the opposite is true: right dogma is of no benefit when one leads a corrupt life." [Οὐδέν ὄφελος βίου καθαροῦ, δογμάτων διεφθαρμένων, ὥσπερ οὐδέ τοὐναντίον, δογμάτων ὑγιῶν, ἐάν ὁ βίος ᾖ διεφθαρμένος» P.G. 53,31 καί P.G. 59, 369]

And elsewhere:

"Let us not think that holding the faith alone is sufficient for salvation, if we do not also show forth a pure life." [Μηδέ νομίζωμεν ἀρκεῖν ἡμῖν πρός σωτηρίαν τήν πίστιν, ἐάν μή βίον ἐπιδειξώμεθα καθαρόν. - P.G. 59, 77]

For him who has a corrupt life it is a matter of time that he will adopt heretical dogmas. And, although we are not to concern ourselves with the corrupt lives of others, we are called to examine the dogma and the faith of others - including bishops. We judge on the basis of that which we have all inherited, both in our Chrismation and in the Holy Tradition.

In Church life today we observe the tragic consequences when clergy and laity ignore the inseparable relation of faith and life, both with the temptation on the left and that on the right. Whether one has shipwrecked in terms of faith or in terms of life, it matters little to the enemy of our salvation. His aim is to remove us from the full life of the Church, to deprive us of the Grace of God and make us into the "world." Whether you exit the Church on the right or the left, he cares not - so long as you exit, so long as you are removed from the Mystery and Mysteries.

5. The Work of Initiating our Children into the Mystery

There is a great pitfall that we can all slip into, following, as we are often encouraged to do, not the illumined and deified (of which there are few) but the academic “experts.” Namely, it is to make the goal of our education μάθηση (fact learning) as opposed to επίγνωσης (experiential knowledge) and μύηση (initiation). The focus of our work becomes producing intellectuals and academics, quite knowledgeable about many things, no doubt, but not initiated into the Mystery.

When the spiritual and intellectual center of our education moves from the altar to the podium, or from the Gospel book to the text book, or from The Prayer to social work, then we have acquired the "form of piety" without "the power thereof". In such a case, the "επίγνωσης of the truth" - the experience of, communion with, Christ - will remain something sought for but never actualized. And then the fearful words of our Lord will be applied:

"Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt hath lost its savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men." (Matt. 5:13)

One cause of falling into this tragic error is the loss of discernment in how to "hierarchize", or prioritize spiritual matters. This error, in turn, is caused by the encroachment of the worldly spirit due to alienation from the ascetic life as the presupposition of participation in the Mystery and Mysteries of Christ.

If we truly wish to be "followers of the Holy Fathers," to be Orthodox in practice, it is necessary that we also be following them in the presuppositions of their dogmatic teaching, which is, namely, their life in the Holy Spirit, the pre-requisite of which is purification from the passions and enlightenment of the intellect through God's divinizing Grace. This purification from the passions is considered of greater importance than theology itself by the great Theologian himself, St. Gregory, for only then can the intellect of man truly come to know God by participation in Him.

In this context, we sadly observe that our contemporary academic theology has (with a few notable exceptions) not followed Patristic theology. The reason for this appears to be because it has been deeply effected by the secularized, heterodox theological environment in the West. In particular, this refers to their theological methodology and mistaken theological presuppositions.

Western Heterodox theological methodology is mainly based upon reductive and abstract functioning of the intellect, which is, in the final analysis, autonomous from God. Thus, in the West, dogmas were mainly considered to be theological ideas which are conceived in the mind without any particular relation to the life of the one expressing it. On the contrary, Orthodox theological methodology is experiential, characterized by living knowledge of God which is actualized within the Church, the communion of theosis.

Therefore, it should be clear why the Holy Fathers, although valuing θύραθεν / human wisdom, knew its proper place and did not allow it to supplant the central place which ἄνωθεν / divine wisdom occupies, and while engaging in theological discourse they never lost sight of the spiritual presuppositions.

Today, one observes generally that there is confusion or ignorance as to the hierarchy of things in spiritual and intellectual life, including in home education. In order for everything to ultimately serve our ascent, however, it is essential that the hierarchy of things is maintained.

6. The Use of θύραθεν Philosophy in Christian Education Today

What does all of this mean for us today? Is it good for Orthodox children to study the ancient philosophers and read pagan literature, or not? Is there any benefit for Orthodox children? Is there any harm in it?

One possible answer, abrupt as it is, was given by St. Gregory of Nysa, who was no stranger to worldly wisdom. He said: “Secular [or worldly] education, in very truth, is infertile, always in labor, and never giving life to its offspring.” (13)

This is not to say that St. Gregory did not make use of it. As we saw above, the Fathers used it as a tool in their work of upbuilding the Church. The question, then, is not primarily should Orthodox children approach worldly wisdom in search of The Light, as if they do not have Him, but is this worldly wisdom useful? Is it a means to the end or aim of our life?

The answer to these questions is manifest when we answer another, more basic question: what is the true aim of our Christian life? On this, St. Seraphim of Sarov has this to say:

“Prayer, fasting, vigil and all other Christian practices, however good they may be in themselves, do not constitute the aim of our Christian life, although they serve as the indispensable means of reaching this end. The true aim of our Christian life consists in the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God.” (14)

The only Good per se, then, is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit. Among the means to reaching this end one could include spiritual study, of course, but is it good to study θύραθεν philosophy and literature? It could be “good” contingent upon a positive response to this question: does it lead one to the acquisition of the Holy Spirit? (15)

Within the Orthodox spirit and ethos the pursuit of the telos, the end, is ultimately free of the deon, or “duty” or “rules.” This is most apparent in the lives of the “fools-for-Christ.” However, the freedom of holiness presupposes purification from the passions. A salvific use of freedom has as its sine qua non freedom from the passions, usually obtained after long ascetic struggle. For most of us, such freedom is still to come, after we learn obedience to Christ in His Body and under the direction of a spiritual father.

What does this imply for the education of our children and the use of θύραθεν wisdom? In practice it means we make of it selective use for particularly suited children of high school or late high school age. Why? For the same reason that it is unwise to expose a newly planted tree to high winds and rain without it first putting down roots: it will most likely be uprooted. As homeschooling parents the truth of this should be obvious to all of us, for on this same basis we also decided not to send our young souls into the storm of public schools.

Putting down roots here means a thorough grounding in the realism of the Holy Scriptures and Lives of the Saints, and years living within the grace of God and under the shelter of obedience to a spiritual father. Thus, when they are exposed to the gusts of the ‘natural man’s’ philosophy and the rain of idolatrous fancy they will weather the storm and be the better for it.

And, yet, even this discerning use of worldly wisdom and pagan literature is not a necessity, nor recommended for some. As we saw above, even St. Basil the Great, who had the task to guide young men through the wilderness of pagan literature, realized late in life that there was no need for him to do it for his salvation. The narrow path is winding, to be sure, but one does not need to pass through Athens to reach Jerusalem. If some do, for whatever historical or pastoral or intellectual reason, that is another matter, and it may be, as it was in St. Basil’s case, providential and ultimately for the upbuilding of the Church.

Here, someone might respond: not everything has to serve the aim of the acquisition of the Holy Spirit, does it? How about just fulfilling the need for students to develop intellectually, read, write and speak well, become good citizens, function in society, etc.?

Undoubtedly, there is need of developing these skills and gifts. That is why, ultimately, the particulars of the decision belong to the parents, who will decide on a case by case basis when and how much of the wisdom offered for life in this world is necessary and beneficial for their children’s’ mental and educational development. (16)

In the process of discernment, however, let them not acquiesce to the proud thought that ALL of my children must be well-versed in the wisdom of this world in order to go to college. Or, ALL of my children must become professionals or teachers. This thought, inspired from the demon of pride on the right, has led many an innocent soul into the fire of fornication and darkness of disbelief. Beyond the sad reality of the university today, the system of which has been rightly labeled the Gulag Pelagos of America, this is an abysmal and impersonal pedagogy which sets some children up for miserable lives, even as it serves to further the diabolical aims of globalization.

No, we must remain focused on each child’s gifts and spiritual condition, guiding and correcting our course analogous with the spiritual conditions, but always with the telos, or end, in mind: purification from the passions and illumination of the nous.

This brings us to one final question with regard to worldly wisdom: can one find enlightenment towards salvation in the writings of the ancient Greek philosophers or in the men of letters among the heterodox, in terms of the process of purification of the soul?

It should be clear at this point that for whatever reason we utilize the wisdom of the world in the education of our children, its function is only preparatory for the spiritual life. Although a honing of the mind can purify one of wrong thinking about reality, the purification of the passions of the soul has spiritual presuppositions which cannot be fulfilled by even the greatest refinement of the rational intellect, much less the imagination, for purification toward illumination pertains to the nous and its cleansing.

1 See the Letter of Metropolitan Paul of Glyfadas who succinctly presents the matter, here: https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2012/03/contextual-or-post-patristic-theology.html

2 Demetrios Tselingidis, Post-Patristic or Neo-Barlaamite Theology (http://orthodox-voice.blogspot.nl/2013/05/patristic-theology-and-post-patristic.html).

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 From an article by Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos) entitled: “Barlaamism in Contemporary Theology (https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2014/10/barlaamism-in-contemporary-theology-1.html).

6 Evagrius Ponticus, Chapters on Prayer, chapter 60.

7 https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2014/10/barlaamism-in-contemporary-theology-2.html.

8 “To the youth; on how they can benefit from Greek [pagan] literature” (Πρὸς τοὺς νέους, ὅπως ἂν ἐξ ἑλληνικῶν ὠφελοῖντο λόγων [De legendis gentilium libris]).

9 See: St. Gregory’s works Contra Julianum Imperatorem - Κατά Ἰουλιανοῦ Βασιλέως στηλιτευτικοὶ 1 & 2.

10 St. Photios the Great. Amphilochios. Question 107. See: Protopresbyter Theodore Zisis, Following the Holy Fathers (New Rome Press, 2017), p. 186.

11 Ibid. Question 202; Zisis, p. 186.

12 Ibid.

13 St. Gregory of Nysa, De Vita Moysis, II, 36.

14 Trans. Hieromonk Seraphim (Rose), Little Russian Philokalia, Vol.1: St Seraphim, 4th ed. (Platina, CA: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1996), p.79.

15 With respect to these and subsequent reflections, I am indebted to Deacon Aaron Taylor for his study, Reading Imaginative Literature: A Study in Orthodox Moral Theology.

16 As St John Chrysostom writes, “It is impossible to treat all…people in one way, any more than it would be right for the doctors to deal with all their patients alike.” Περί ιεροσύνης, VI.4 [PG 48]; St John Chrysostom, Six Books on the Priesthood, trans. Graham Neville (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary, 1977), p. 142.

Please be kind, lest your comment go the way of Babylon.