The tradition of Orthodox Christian women wearing veils is and always has been part of the Eastern Orthodox Church. This tradition can be found in the Scriptures written by St. Paul, the Patristic Fathers such as St. John Chrysostom, and in Orthodox iconography which exhibits what we believe theologically. The veiling of Orthodox women during the liturgical services of the Church is one of the first things a visitor or inquirer might notice when coming to an Orthodox parish.

Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, there are many women in the Church today who are not following this ancient and pious Orthodox Christian tradition. First and foremost, many do not know simply because they have never been taught. Additionally, many have been negatively influenced by secular culture and the unfortunate effects of modernism that is encroaching upon our parishes. Veiling is often seen as oppressive, outdated, and even irrelevant to many female parishioners who have not acquired the Orthodox phronema and have not established an experiential Orthodox ethos. Many of these women have been influenced by heretical modernist feminism, or worse, think that veiling is some oppressive Islamic practice that has crept into the tradition of the Church.

For many clergy, this subject carries a certain sensitivity. Oftentimes bishops and priests avoid speaking about veiling for fear of angering or offending women in the parish or fear they will come across as misogynistic for upholding the traditions of the Church. However, this fear and avoidance on the part of the clergy is doing a disservice to the women attending the divine services. Is it not the duty of the clergy to give the proper catechesis no matter how uncomfortable it might be to the so-called “modern woman”?

As mentioned above, the veiling of Orthodox women has its origins in apostolic times, patristic writings, and the iconography of the Church. It is a good and pious practice that all women in the Holy Orthodox Church should adopt and embrace veiling as their God given "sign of authority on her head" (1 Corinthians 11:10). The specific traditionally ethnic jurisdiction a woman finds herself in is irrelevant. We can first see the apostolic and scriptural origins of the head covering of women in the first epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, Chapter 11. St. Paul writes:

“Be ye followers of me, even as I also am of Christ. Now I praise you, brethren, that ye remember me in all things, and keep the ordinances, as I delivered them to you. But I would have you know, that the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God. Every man praying or prophesying, having his head covered, dishonoureth his head. But every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoureth her head: for that is even all one as if she were shaven. For if the woman be not covered, let her also be shorn: but if it be a shame for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered [...] For this cause ought the woman to have power on her head because of the angels. Nevertheless neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord." [1]

Scriptural commentaries of St. John Chrysostom, the 5th century Patriarch of Constantinople and the author of our Divine Liturgy, give us a very in-depth and clear explanation of what St. Paul means when he commands women to have their heads covered. St. John Chrysostom writes:

“But the woman he [St. Paul] commands to be at all times covered. Wherefore also having said, ‘Every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head unveiled, dishonoreth her head,’ he stayed not at this point only, but also proceeded to say, ‘for it is one and the same thing as if she were shaven.’ But if to be shaven is always dishonorable, it is plain too that being uncovered is always a reproach. And not even with this only was he content, but added again, saying, ‘The woman ought to have a sign of authority on her head, because of the angels.’ He signifies that not at the time of prayer only but also continually, she ought to be covered […] ‘If a woman is not veiled, let her also be shorn: but if it be a shame for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be veiled.’ Thus, in the beginning he simply requires that the head be not bare: but as he proceeds he intimates both the continuance of the rule, saying, ‘for it is one and the same thing as if she were shaven,’ and the keeping of it with all care and diligence. For he said not merely covered, but ‘covered over,’[οὐδὲ γὰρ καλύπτεσθαι, ἀλλα κατακαλύπτεσθαι]. Meaning that she be carefully wrapped up on every side. And by reducing it to an absurdity, he appeals to their shame, saying by way of severe reprimand, ‘but if she be not covered, let her also be shorn.’ As if he had said, ‘If thou cast away the covering appointed by the law of God, cast away likewise that appointed by nature.’” [2]

As we can see from the commentary by St. John Chrysostom, it was expected of all women to be covered not only during liturgical periods of prayer, but at all times, for this was their honor and sign of authority given by our Lord. St. Augustine of Hippo, the famous North African hierarch of the 5th century, states in Letter CCXLV [245] to Possidus that “those who belong to the world have also to consider how they may in these things please their wives if they be husbands, their husbands if they be wives; with this limitation, that it is not becoming even in married women to uncover their hair, since the apostle commands women to keep their heads covered.” [3]

What is common among these saints and many others is that when speaking of women veiling their heads, it is not just in reference to their liturgical life in the Church but in all aspects of daily life. In another example, Didascalia Apostolorum, a little known but ancient document on Church Order, was “originally composed in Greek c. 230 in northern Syria,” writes scholar Gabriel Radle, “possibly by a bishop, alludes to some of the same preoccupations about the exposure of women’s bodies, including their heads.” The author of Didascalia Apostolorum admonishes women not to dress their hair “with the hairstyle of a harlot,” but instructs them, “when you walk in the street cover your head with your robe so that your great beauty is concealed by your veiling.” [4] During these ancient times the saints called women to adhere to the apostolic tradition and veil themselves while going about everyday life; how much more would they expect women to absolutely cover their heads in the presence of Christ during the Divine Liturgy when the priest calls down the Holy Spirit and brings about the change to the Holy Gifts that gives us life eternal?

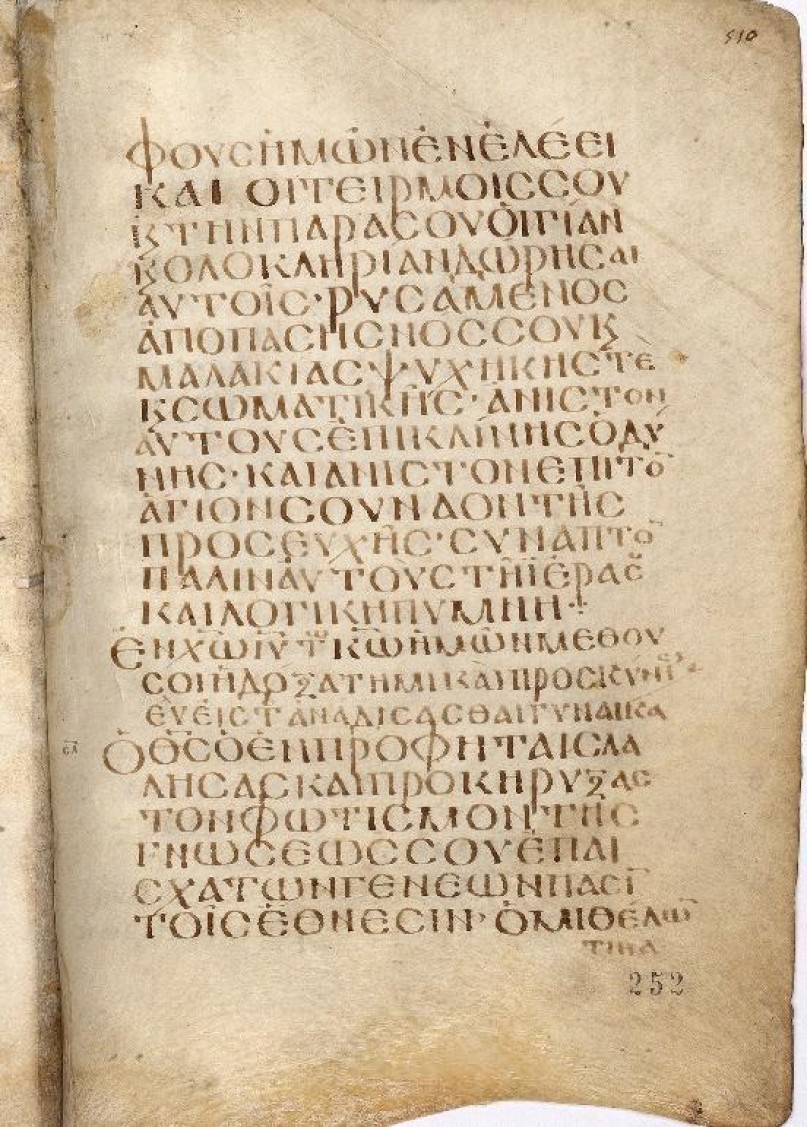

Veiling of Orthodox Christian women can also be seen in the prayers of the Church. In what are called “euchologion (εὐχολόγιον), or euchology,” Radle writes, “the prayer book used by bishops and priests for public liturgies and private blessings” a prayer called the “binding up the head [hair] of a woman” can be found. [5] These manuscripts (see Figure 1) with this particular prayer appear in various euchologia spanning from 8th century Constantinople to 11th century Palestine. The prayer of the binding of the hair of a woman reads:

Εὐχὴ εἰς τὸ ἀναδήσασθαι γυναῖκα:

Ὁ θεὸς ὁ ἐν προφήταις λαλήσας καὶ προκηρύξας τὸν φωτισμὸν τῆς γνώσεώς σου ἔσεσθαι ἐπ᾽ἐσχάτων γενεῶν πᾶσιν τοῖς ἔθνεσιν, ὁ μὴ θέλων τινὰ τῶν ἐκ τῶν χειρῶν σου πεπλασμένων ἀνθρώπων ἄμοιρον τῆς σωτηρίας, ὁ διὰ τοῦ σκεύους τῆς ἐκλογῆς σου Παύλου τοῦ ἀποστόλου ἐντειλάμενος πάντα εἰς δοξολογίαν ποιεῖν ἡμᾶς τὴν σήν, καὶ νόμους ἐκθέμενος δι᾽ αὐτοῦ τοῖς ἀνδράσιν τοῖς ἐν πίστει πολιτευσαμένοις ὁμοίως δὲ καὶ ταῖς γυναιξίν, ἵνα οἱ μὲν ἄνδρες ἀκατακαλύπτως τὴν κεφαλὴν προσφέρωσίν σοι αἶνον καὶ δόξαν τῷ ἁγίῳ ὀνόματί σου, αἱ δὲ τῇ πίστει σου καθωπλισμέναι γυναῖκες κατακεκαλυμμέναι τὴν κεφαλὴν μετὰ αἴδους καὶ σωφροσύνης κοσμῶσιν ἑαυτὰς ἐν ἔργοις ἀγαθοῖς, καὶ ὕμνους καὶ προσευχὰς προσάγωσιν τῇ δόξῃ σου· αὐτός, δέσποτα τῶν ἁπάντων, εὐλόγησον τὴν δούλην σου ταύτην καὶ κόσμησον τὴν αὐτῆς κεφαλὴν κόσμον τὸν ἐν σοὶ εὐάρεστον καὶ ἐράσμιον, εὐσχημοσύνην τε καὶ τιμὴν καὶ εὐπρέπειαν, ὅπως κατὰ τὰς ἐντολάς σου πολιτευσαμένη καὶ τὰ μέλη πρὸς σωφρονισμὸν παιδαγωγοῦσα, τύχῃ τῶν αἰωνίων σου ἀγαθῶν σὺν τῇ ἀναδηνούσῃ αὐτήν. Ἐν Χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ τῷ Κυρίῳ ἡμῶν μεθ᾽ οὗ σοὶ δόξα σὺν τῷ παναγίῳ καὶ ἀγαθῷ καὶ ζωοποιῷ σου πνεύματι νῦν καὶ ἀεί.

Prayer for binding up (the head of) a woman:

O God, you who have spoken through the prophets and proclaimed that in the final generations the light of your knowledge will be for all nations, you who desire that no human created by your hands remain devoid of salvation, you who through the apostle Paul, your elected instrument, ordered us to do everything for your glory, and through him you instituted laws for men and women who live in the faith, namely that men offer praise and glory to your holy name with an uncovered head, while women, fully armed in your faith, covering the head, adorn themselves in good works and bring hymns and prayers to your glory with modesty and sobriety; you, O master of all things, bless this your servant and adorn her head with an ornament that is acceptable and pleasing to you, with gracefulness, as well as honor and decorum, so that conducting herself according to your commandments and educating the members (of her body) toward self-control, she may attain your eternal benefits together with the one who binds her (head) up. In Jesus Christ our Lord, with whom to you belongs glory together with the most holy, good and life-giving Spirit, now and ever (and unto the ages of ages). [6]

On this rite Gabriel Radle says, “The manuscript evidence does not provide any indication concerning the particulars of the performance of this rite, such as the occasion and circumstance for which it is intended. The manuscripts simply include the title and text of the prayer (εὐχή). This convention is typical among the earliest sacramentaries of both East and West. This service book was primarily intended to provide a bishop or priest with the words to pronounce during a religious service, leaving us to hypothesize about the ritual aspects that are taken for granted by the scribes and users of these books. Although no scholar has attempted a detailed study of the rite, the few who have noted it have proposed different theories as to its origin and meaning.” [7] While we may not know exactly when and how this prayer was used, in reading the prayer with an Orthodox mind and within the context of the Orthodox Church we can clearly see that the veiling of women was blessed in a liturgical context.

In addition to the various scriptural, patristic, and historical examinations presented above, let us also look to Orthodox Christian iconography and see what the Church teaches concerning the veiling of Orthodox Christian women. Icons are windows into our theology and portray the holy ones who stand at the throne of God and whom we are called to imitate. As Father Peter Heers can be quoted time and again saying, “we follow the saints!” If one looks at almost any icon of a female saint we will see that the saint is almost always wearing some type of veil, crown, or both, as in the examples of St. Tamara of Georgia and other righteous female monarchs. Notice that in the first icon below (see Figure 2) all of these female saints have their heads covered. In the icon of the Synaxis of Female Saints (see Figure 3), again you notice all have their head covered with the exception of a few, such as St. Mary of Egypt whose clothes disintegrated during her extreme period of asceticism and repentance in the desert where she had only the cloak of St. Zosimas.

The final question for Orthodox Christian women reading this is to ask: what do the monasteries tell us? After all, our holy monastics are traditionally the ones who have upheld the true Orthodox faith at all times throughout the Church’s history, even when storms raged both within the Church and from without. The view of the majority of all monasteries is that women are required to be veiled while visiting. If this standard is being taught by our holy monastics, shouldn’t this be carried over to our parish life?

Holy Trinity Monastery of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia stipulates that “No one wearing shorts or dressed immodestly should enter the grounds of the monastery. Women wishing to enter the church are kindly asked to wear a head covering and a skirt or dress” (see Figure 4). [8] St. Anthony’s Monastery in Florence, Arizona, founded by Geronda Ephraim of Philotheou and Arizona, stipulates that “Women are kindly asked to wear long-sleeved, loose-fitting shirts that fully cover the chest up to the neck; long skirts (or dresses) without deep slits; scarves that cover the head and wrap under the chin and around the neck, so that the neck is also covered. Please refrain from wearing lipstick when venerating icons and receiving Holy Communion.” [9] St. Nektarios Greek Orthodox Monastery in New York stipulates that “Women must wear long skirts, long-sleeved blouses, and cover their head with a scarf.” [10] St. John the Forerunner Greek Orthodox Monastery in Washington State stipulates that “Guests should be dressed modestly: […] women in long sleeves, long skirts and head coverings.” [11]

It is our duty as Orthodox Christians to obediently follow what has been given us by Holy Tradition. St. Paul writes to the Church in Thessalonica: “Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions which ye have been taught, whether by word, or our epistle.” [12] Without a doubt the tradition given to us is the tradition of Orthodox Christian women veiling in church. This God-pleasing practice is not only in the Scriptures themselves, but also in the patristic witness of the Church Fathers and in the historical record of the Church throughout her existence. St. Paul, the Fathers of the Church, and female saints by their example did not exhort us to hold on to anti-Christian and modernist traditions, concepts, ideologies, or politics concerning the veiling of women in the Orthodox Church. It is time for Orthodox Christian women everywhere to pick up the mantle of Holy Tradition and embrace this pious practice for their salvation and the salvation of women of the next generation. May the example of our Most Holy Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary and all of the female saints be the standard-bearers for all women in the Church today.

References

[1]. 1 Corinthians 11:1-6, 10-11, KJV

[2]. St. John Chrysostom, “St. Chrysostom: Homilies on the Epistles of Saint Paul to the Corinthians: Homily XXVI,” Nicene & Post Nicene Fathers (Peabody: Hendrickson Publications, 1990), 149.

[3]. St. Augustine of Hippo, “Letter CCXLV,” Nicene & Post-Nicene Fathers (Peabody: Hendrickson Publications, 1990), 588.

[4]. Gabriel Radle, “The Veiling of Women in Byzantium: Liturgy, Hair, and Identity in a Medieval Rite of Passage,” Speculum 94, no 4. (October 2019):17.

[5]. Ibid, 3.

[6]. Ibid, 5-6.

[7]. Ibid, 6.

[8]. “Visitor Info,” Holy Trinity Monastery Russian Orthodox Monastery, accessed August 23rd, 2022, https://jordanville.org/visitorinfo

[9]. “Daily Visitors Guide: What to Wear,” St. Anthony’s Greek Orthodox Monastery, accessed August 23rd, 2022, https://stanthonysmonastery.org/pages/day-visitors...

[10]. “Visiting Hours and Dress Code,” St. Nektarios Greek Orthodox Monastery, accessed August 23rd, 2022, https://www.stnektariosmonastery.org/en/visitingho...

[11]. “Visitor Information: On the Grounds,” St John the Forerunner Orthodox Monastery, accessed August 23rd, 2022, https://stjohnmonastery.org/visitor-information

[12]. 2 Thessalonians 2:15, KJV

Please be kind, lest your comment go the way of Babylon.